Witness to Genocide’s Aftermath

Something very weird and disturbing is occurring throughout the former Yugoslavia, and most people in the west remain blissfully uninformed and unaware. The grizzled remains of long missing loved ones are surfacing from beneath the earth at an alarming rate, as though being called upon by a higher power to testify to the unspeakable crimes of the past. The wars and accompanying genocides of the Milosevic era may be mercifully over – at least for the time being – but the reckoning of a decade of horror is still very much underway.

Several mass graves, once hastily planned, dug and intricately camouflaged, are now being gradually identified and exhumed, driven by a fortuitous mix of long suppressed witness testimony, outside political pressures and newly forthcoming evidence. Even the recent unprecedented flooding has loosened long hidden bones and skulls from nearly forgotten massacres.

For most of us, such mass grave scenarios are the stuff of our worst nightmares. But for grieving family members, these ongoing discoveries and exhumations offer flickers of renewed hope for a long awaited if bittersweet reunion with beloved, long missing family members. In that context, I like to say that mass graves are the surreal “gifts” that keep on giving.

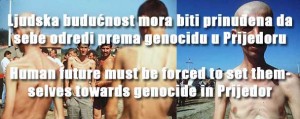

The latest mass graves are by no means new in any historical sense of the word. The huge site in northwestern Bosnia, for example, is located in the village of Tomasica, and probably dates from 1992 or 1993. It lies very near to Prijedor, one of the main centers of Nazi-style concentration camps and mass killing organized by Bosnian Serb forces in the early 1990s, generously funded and supplied by the Milosevic regime from Belgrade, in his monomaniacal campaign for a Greater Serbia.

So far, some 430 victims have been exhumed from the Tomasica site – a vast, cavernous pit about 30 feet deep and covering some 54,000 square feet. This mass grave, like many hundreds of others throughout the Bosnian terrain, contains victims of Serb units who killed thousands of Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) and also Bosnian Croats in hopes of creating an “ethnically pure” region.

Originally, the Tomasica site is believed to have held the remains of up to 1,000 men, women and children, suggesting that some of the bodies were later dug up and moved, all of which complicates the efforts to identify the dead. Forensic teams also discovered bullets inside the grave, strongly indicating that Tomasica served as a site of execution as well.

Deeply disturbing details have emerged on how bodies came to Tomasica. According to a recent investigation, prisoners were taken from the infamous Serb-run concentration camps in Trnopolje and Omarska, and forced to unload bodies from the trucks and toss them into the grave. After finishing their tasks, they were shot on the spot.

The Tomasica grave was found covered by several yards of high artificial mounds, under which another layer of “soil” was discovered, consisting of piled-up earthly remains. The first bodies were found at the depth of some 23 feet. Due to specific soil content, the natural process of decomposition was significantly delayed, and some corpses were found in a bizarrely mummified state. After the grave was unearthed, the stench of death reportedly began spreading throughout the area.

According to Bosnian officials, the site was originally identified last April by two former Bosnian Serb soldiers who helped to determine the exact location of the gravesite. One of the men, presumably suffering ongoing pangs of guilt and remorse, subsequently jumped off a bridge to his death, another senseless victim of the mass murders and genocides.

Ironically, at the very same time the Tomasica site has been yielding up hundreds of long hidden corpses, another long-awaited mass gravesite, some 400 miles to the southeast, is spawning a totally separate but intimately related exhumation. This site at Rudnica is situated by the Serbian town of Raska in the far southern region of the predominantly Bosniak-populated region of Sandzak, not coincidentally just miles from Serbia’s border with Kosova, independent since February 2008.

As of this writing, the remains of some 50 people, all Kosovar Albanians, have been exhumed from the Rudnica site, but scores more are certain to surface. It’s believed the site will eventually yield from 250 to 500 bodies. Unlike past exhumations inside Serbia, this undertaking is being supervised by officials of the International Red Cross, Eulex (European Union Rule of Law), and Kosovar Albanian representatives. It all means no more tricks, no more obfuscation. Despite the superficial transparency, however, no independent media is allowed at the site.

The history of this particular site, actually a complex of sites, is a fascinating one, and an especially sensitive one for this writer. It turns out that the location was known about by NATO officials since 1999, during or shortly after the NATO armed intervention that forcefully ended Milosevic’s brutal crackdown against the ethnic Albanians of Kosova.

At that time, some 800,000 Albanian civilians were driven from their homes and forced to flee. It was a time of mass killing and systematic mass rape on a horrifying scale, involving Serbian army units, “paramilitaries”, police, sympathetic civilians and state security forces. At some point, the order was given from Belgrade to dig up Albanian corpses from hastily created mass graves inside Kosova, and ship them in refrigerator trucks into Serbia proper. Units of Serbian special forces went to work. (Serbian Documentary)

These macabre convoys of corpses made their way across the border and to a variety of ad hoc destinations – some were initially plunged into rivers or lakes, others dumped their loads of human cargo into industrialized furnaces like the factory complex at Mackatica, hastily arranged mass graves like the ones on police-training grounds just outside of Belgrade, or sites like this one at Rudnica. Over the past decade, the remains of nearly 1,000 men, women and children have been gradually returned to Kosova. That group included small babies, some with pacifiers still in their mouths.

Since 1999, successive regimes in Belgrade managed to keep the Rudnica gravesite unmolested and unexamined. The most egregious cover-up episode occurred in 2010, after the BBC and other prominent news sources exposed the suspected site in some detail, describing how “a small building stands directly over the bodies – its foundations deliberately constructed to hide the site.”

The following month, my Albanian colleague and I wrote an article entitled “The Dead Bear Witness” (Mass Grave Report) detailing specifics of the mass grave and demanding that a proper, internationally-supervised exhumation be immediately undertaken. Instead, Serbian authorities sent in their own “expert” team that allegedly undertook a soil sampling from nearby the building and promptly declared the results “negative” for organic matter.

The Serbian alternative press Pescanik offers a slightly different version of events. They claim that following the soil pseudo-analysis, a 50-page study was submitted by the Faculty of Civil Engineering in Belgrade, which “allegedly proved beyond any doubt that there are no bodies on that location.” Belgrade’s notoriously sycophantic mainstream media quickly trumpeted the propaganda triumph: “Only mass lies,” it declared, “were dug out.”

Knowing Serbia’s less than candid modus operandi, my colleague and I were determined not to let things end there. We proceeded to push our case to various Eulex officials in Kosovo, and then to fellow journalists, first in Belgrade and then in Pristina. No one seemed particularly interested or moved by our entreaties or reports.

We eventually took our case directly to Belgrade, using a lucky invitation extended to my colleague by a sympathetic Serbian journalist. In the summer of 2011, we attended a press conference at Belgrade’s impressive new media center, focusing on Serbia’s controversial negotiating team with Pristina. In a memorable scene of cinematic-like high drama, after we dared to introduce a copy of our latest war crimes report, dozens of assembled journalists suddenly began treating us like dangerously contagious lepers. (War Crimes Report)

One audience member, presumably a hard-core Serbian nationalist, immediately rose to denounce us: “They were recently spotted with an Albanian irredentist,” she declared in Serbian, pointing to the two of us. (We had just come from a series of meetings with Albanian politicians in Preseva, in southern Serbia).

It suddenly felt as though we’d just been denounced at a central committee meeting of the Serbian Communist party. Needless to say, copies of our report were never picked up by any of the assembled journalists or politicians. My colleague’s journalist friend mysteriously disappeared. Lesson learned: telling the truth about Serbia’s onerous past will not make you popular in Belgrade.

I have no doubt that Eulex officials could have applied stronger, more vigorous pressure on Belgrade officials; the media in either Serbia or Kosova could also have launched appropriate public informational campaigns. Instead, we came up against a broad apathy bordering on moral acquiescence. I found myself trapped in a kind of Balkan Alice-through-the-Looking-Glass nightmare. Following the May 2010 breakthrough, it took another three and a half years for a serious exhumation of Raska to finally begin.

But that’s not quite the entire story. According to Pescanik, before the exhumation could actually commence, Serbian authorities hit up Kosovar authorities for 300,000 euro – over 400,000 US dollars – for ‘financial coverage’ of the investigation, including the funds for demolition of the building constructed to camouflage the mass grave. Talk about adding insult to injury. With the expenses pre-paid and additional, significant EU pressures gradually brought to bear, Serbia was finally read to act. In November 2013, the current exhumation process began to proceed.

At the very time Tomasica and Raska were still being exhumed, yet another troubling and unexpected discovery occurred, this time in eastern Bosnia. The recent, unprecedented flooding had unearthed another secret mass grave, this one containing the remains of at least six people, including four complete bodies whose hands were found tied behind their backs. Once again it is believed these victims are Bosniaks, this time from around the town of Doboj, part of a long sought after group of massacred civilians.

All in all, some 100,000 people died in the Bosnian war, the majority being targeted Bosniak civilians. At Srebrenica alone, 8,000 Bosniak men and boys were hunted down and butchered like animals. Even the ever-cautious Hague tribunal officially classifies Srebrenica as a genocide.Thousands of Bosnians remain missing, and many will never be found.

In Kosova, from 1998 – 1999, up to 13,000 ethnic Albanians were killed, along with over 1,000 members of other ethnic groups. Some 1700 persons still remain missing, mainly ethnic Albanians, but also Serbs, Roma and members of other minority groups. All of their surviving loved ones still await some kind of closure – each family has the right to a respectful and dignified funeral, even if they are burying only long-degraded skeletal remnants and bone fragments.

With all of these seemingly endless mass grave exhumations and discoveries, it would seem next to impossible for anyone to still pretend that during the 1990s, no genocide occurred targeting Bosniaks or ethnic Albanians in Kosova. The mounds of physical evidence, of corpses and fragmented skeletons, not to mention testimony from multiple war crimes trials, is absolutely overwhelming.

Of course members of all ethnic groups suffered terribly, and isolated crimes were committed by all sides. “No side,” one Bosniak survivor of a concentration camp insisted to us, “has completely clean hands.” But that does not erase the underlying genocide – nor allow the perpetrators some kind of free moral pass. Ever.

A group of colleagues and I, deeply frustrated by the seemingly endless genocide denial, have begun early, tentative preparations for the creation of a special peace center in the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo, dedicated to the robust documentation of past genocides, and to the prevention of genocide around the world. We plan to name the center after Anne Frank, a universally beloved figure, and a potent symbol of resistance to tyranny. For my own family, Polish Jews hunted down and murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust, the insistent act of remembrance and the struggle to prevent future such horrors bears a powerful resonance.

For people the world over, so many indelibly affected by the twin evils of genocide and genocide denial, a peace education center in multicultural Sarajevo could be the greatest gift of all.

Robert Leonard Rope

Member of the International Expert Team of the Institute for Research Genocide, Canada