Conspicuous war crimes trial against a Bosnian in Belgrade

The former military personnel Osman Osmanović from Bosnia-Herzegovina is being tried in Belgrade. Although the evidence is very weak, he was convicted in the first instance. On November 23rd, 2019, he lost his freedom. Back then Osman Osmanovć was arrested on the Serbian border while trying to travel from Bosnia-Herzegovina to Serbia. He has been in custody in Belgrade for two and a half years now because he is not a Serbian, but a Bosnian citizen. His arrest is based on a single crime, at the time without a warrant or charge. However, the Serbian authorities argued that there was a risk of absconding. Osmanović is accused of inhumanly treating, unlawfully detaining, torturing, and committing violence against four people in the Rasadnik camp near the Bosnian city Brčko during the Bosnian war in May and June of 1992. Three of the four victims named by the court have already died.

Only one victim testified

Therefore, only Vasiljko Todić could testify. He stated that he was held in Gornji Rahić for 83 days and that the prisoners were accommodated in the former cold store Rasadnik without any sanitary facilities. Due to poor nutrition, he lost a lot of weight. Todić also testified that Osmanović was present at his interrogation in Rasadnik. At the time, Osmanović told him “You’re lying, Chetnik!”, and hit him in the face. There are only statements from third parties about the three deceased victims. The witness Mara Vukmirović, daughter of the late former prisoner Aleksandar Pavlović, testified that Osmanović was present when an inspector kicked Pavlović in the knee. The witness Snježana Simikić, half-sister of the late former prisoner Milenko Radušić, testified that her brother never said who hit him.

Possible revenge motive

The witness Zora Simić, wife of the late Rado Simić, said her husband never named Osmanović. Despite that, Osmanović was sentenced to five years in prison in the first instance in mid-March. And despite an appeal, he is still not allowed to be released. Osmanović himself stated that during the war he was responsible for public security in Brčko as part of the Interior Ministry of Bosnia and Herzegovina. He interrogated Pavlović and Radušić, but he did not know Todić and Simić. He met Pavlović again after the war. Osmanović also stated that Pavlović shouldn’t have been imprisoned in the camp. The defendant further stated that he suspected that he had been accused because he won a lawsuit for damages against the newspaper “Press”. “Press” released an article in which he was blamed for torturing Serbians in the camp of Gornji Rahić. Another reason for the indictment, in his view, was his activity after the war.

Fight against organized crime

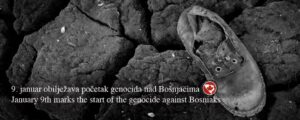

Osmanović was the head of the Department for Combating organized Crime in the Interior Ministry of Tuzla Canton and had conducted investigations against the government. Ministers, municipal leaders, and directors of public companies were examined. While he was director of the tax office, Osmanović had investigations against several department heads in Brčko. One of them, who was actually charged, swore at that time that he would take revenge on him. Now it is completely undisputed that crimes were committed against the Bosnian Serb prisoners in the Rasadnik camp. Rasadnik was actually a cold store made of corrugated iron located in Okrajci in Gornji Rahić near Brčko and was used as a detention room for Serbian prisoners of war and civilians in May and June 1992. The camp was under the command of the Croatian Territorial Defense and the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The circumstances were inhuman. There were no windows, no sanitary facilities, and the food brought to the prisoners was so little and bad that they lost a lot of weight.

Two convictions

The prisoners were abused and tortured. Police inspector Galib Hadžić and a Croatian territorial defense representative, Nijaz Hodžić, were sentenced to two years and ten months, and one year in prison, respectively, for crimes against Serbian civilians and prisoners of war in that very camp. Nevertheless, it is questionable whether Osmanović committed these acts because the evidence is conspicuously weak. The jurisdiction of the Serbian court is also strange in this case. Because Osmanović is a Bosnian citizen, and the act alleged against him is said to have been committed on the territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina and not in Serbia, and the alleged victims are also Bosnian citizens residing in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Now, a Serbian court can also punish war crimes, which were committed in the neighbouring state. However, in other war crimes investigations, which are very similar, the cases have been handed over to the Bosnian judicial authorities.

Proceedings transferred to Bosnia

The public prosecutor of Bosnia and Herzegovina therefore asked Serbia to hand over the accused, but the court in Serbia refused. Osmanović is one of three Bosnian citizens arrested between 2018 and 2021 trying to cross the border from Bosnia-Herzegovina to Serbia. The Humanitarian Law Centre in Belgrade argues that “concerning the intensification in regional cooperation which is necessary for an efficient prosecution of all suspects, but also for building the confidence of the victims, these proceedings should have been transferred to Bosnia and Herzegovina.” It also points out that the court wrongly anonymized the indictment and violated its own rules.

No fair process

Osmanović’s relatives believe that the trial is politically motivated and a continuation of Serbia’s aggressive policy of interfering in the internal affairs of Bosnia and Herzegovina and engaging in persecution of its citizens. In fact, some courts in Europe have already prohibited the extradition of Bosnian citizens to Serbia – despite corresponding arrest warrants – because they argued that the accused could not count on a fair trial in Serbia. The most prominent case was probably that of the Bosnian ex-general Jovan Divjak, who was arrested in Austria in 2011 on a basis of an arrest warrant from Serbia. Divjak was a thorn in the side of many nationalists in Serbia, because as a Serb, he had defended the city of Sarajevo during the war and had not sided with the Serbian nationalists, who shelled and besieged the city for three and a half years. The Korneuburg Regional Court ruled in 2011 that the late Divjak should not be extradited to Serbia, because he couldn’t expect a fair trial there. Especially when it comes to alleged war crimes, political agendas are always involved in South-eastern Europe. But Serbia’s judicial system is also beyond that and in need of reform overall.

“External pressure on judges”

According to the latest report by the organization Freedom House, “independence of the judiciary in Serbia is hampered by political influence over the appointment of judges”. Many judges “reported that they are exposed to external pressure in their judgements”. Politicians in Serbia also regularly commented on judicial matters. Corruption, lack of capacity and political clout sometimes undermine a fair trial, Freedom House said. “Among other problems, the rules for randomly assigning cases to judges and prosecutors are not consistently followed,” the report says.

“High-profile, political sensitive cases are particularly vulnerable to interference.”

(Adelheid Wölfl, 17.05.2022)